JOHN S. ALLEN'S BICYCLE FACILITIES, LAWS AND PROGRAMS PAGES |

||

|

Top: Home Page Up: Bicycle facilities |

|

JOHN S. ALLEN'S BICYCLE FACILITIES, LAWS AND PROGRAMS PAGES |

||

|

Top: Home Page Up: Bicycle facilities |

|

"Blue lane": really a lane,

|

The Cambridge, Massachusetts blue lane

Lane?Lanes can not cross one another outside an intersection. So, if the blue lane here is actually a lane, then the right turn lane can not be continuous. The right turn lane is then actually two lanes -- a lane which tapers down to nothing before the blue lane and another which tapers up from nothing after the blue lane. The first Cambridge right turn lane is to the left of the blue (bike) lane, which is primarily a through lane -- no course for right-turning bicyclists is indicated, an omission which leads to some confusion, as has been described on the page about the Cambridge blue lane. Right turn lanes are normally to the right of all other lanes, but the motorist who wishes to turn right is forced into a merge similar to that from a left-side on-ramp on an expressway -- only more confusing: the motorist must merge across the blue lane from the first, abortive right turn lane into the second one. A motorist who can not complete this merge because a bicyclist appears unexpectedly has no escape route except into the through travel lane to the left, which may already be occupied. In the photo, you can see that the City has forced the through travel lane over to the right with a "gore" (painted median strip) in the middle of the street. In a merge from a left-side expressway on-ramp, the motorist usually has an escape route, onto the highway shoulder or median. Diagonal crosswalk?Crosswalks and travel lanes can occupy the same space on the road surface, and so the right turn lane can be considered continuous if we think of the blue lane as a crosswalk. Traffic in the street is required to yield to all traffic in a crosswalk, and so the requirement for motorists to yield to bicyclists in the blue lane is consistent with its being treated as a crosswalk. But the low diagonal angle of the blue lane and the speed of bicycle traffic, comparable with -- often faster than -- the motor traffic, are not consistent with normal crosswalk design. Crosswalks are for slow, pedestrian traffic. The entries to crosswalks are at locations where motorists are able to see the pedestrian traffic in order to yield to it. That is not the case with a bicyclist to the rear of a motorist in the diagonal bike lane. Let's examine that problem further. The right rear blindspot problemAs long as motor traffic is moving faster than the bicyclists in the blue lane, a motorist is able to see the bicyclists in order to yield to them -- though a motorist may not necessarily expect or be able to yield to a bicyclist who swerves out from the curb without yielding. Such swerving is not normal behavior, and in Massachusetts, its legality is questionable even at the blue lane installation. But also, suppose that a bicyclist is traveling faster than the motor traffic, or at the same speed. Then the bicyclist is in the motorist's right rear blindspot. Under the normal rules of the road, the bicyclist is required to yield. However, in the blue lane, the motorist is required to yield. Suppose, for example, that one bicyclist in the blue lane has almost finished crossing in front of a van in the right turn lane, when another bicyclist swerves out in front of the van. The van's driver is paying attention to the first bicyclist, not looking into his right rear-view mirror. The van speeds up and strikes the second bicyclist, whom the motorist did not see. Under the normal rules of the road, the overtaking bicyclist is required to yield. In the blue lane, the motorist is required to yield. But the motorist did not see the overtaking bicyclist. A similar problem can occur with ramps that enter from the left on an express highway. Highway engineers avoid such ramps, or at least construct them so that the entering drivers are traveling at the same speed as the traffic on the highway before they must merge. The drivers can then pull forward or back slightly to fall into line between vehicles to their right. The blue lane does not reliably offer this opportunity. The merge occurs at a prescribed location, and the motor traffic may easily be traveling more slowly than the bicycle traffic, so motorists do not see the bicyclists to whom they are required to yield. All in all, then, the blue lane is neither a properly designed lane nor a properly designed crosswalk, neither fish nor fowl. The Portland studyA study from Portland, Oregon sang high praise of blue lanes which had been installed there, but it also showed the following statistics:

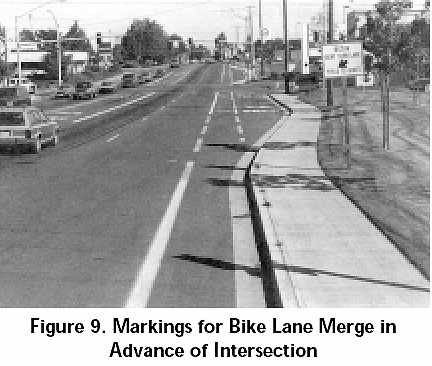

The reduction in caution of bicyclists as shown in the first four rows in the table above is not merely an issue of efficiency; it is one of safety. So is the reduction in motorist use of turn signals: In every one of the Portland blue lane locations the motorist is required by law to use a turn signal. Increase in yielding by motorists reflects a reduced hazard to bicyclists who do not yield, but also reflects increased delay when it would have been more efficient overall for the bicyclists to yield. That motorists slowed more is an indication of reduced efficiency, if the bicyclists' yielding would have resulted in less overall delay. However, note that the motorist and bicyclist percentages of yielding add up to 100% both before and after the blue paint was added. The counting procedure which produced this result requires some further explanation, as both the motorist and bicyclist may attempt to yield (the "Alphonse and Gaston" situation), neither may yield, or there may be nobody to whom to yield. According to Oregon law, a motorist must always yield to a bicyclist in a bike lane. This unusual law gives bike lanes the status of crosswalks, allowing them to overturn the normal vehicular rules of the road, in spite of the sight line problems described above. Oregon law also requires bicyclists to use bike lanes where they exist. In several of the Portland blue lane installations, these laws prohibit bicyclists from following a normal vehicular route, requiring them instead to swerve across motor traffic without the opportunity to merge. The Portland study compared existing bike lane installations before and after blue paint and additional signage were added. There was no comparison with the situation before the bike lanes were installed. Most of the Portland installations involve situations in which standard traffic law would require the bicyclist to yield. Some of the installations crossed entrance and exit ramps, following a course where only a crosswalk could normally be installed. A normal vehicular movement would not be possible while following these blue lanes. The Portland study contains only anecdotal information about crash rates at the Portland installations. Instead, it refers to a European study which claims reductions of crashes in blue lane installations -- but those are not comparable with the Portland installations. Most of the European installations are at entrances of cross streets along urban streets with low-speed traffic, and some are along sidepaths that conflict with all turning traffic. Some sidepaths also feature a raised road surface as in a speed table, forcing motorists to slow. Another problem in making comparisons with this European study is that the car-bike crash rate for sidepaths is very high compared with travel on the roadway (see pages about sidepaths), and so the baseline data are not comparable. Several of the Portland installations are at locations which novice bicyclists find intimidating, such as Interstate entrance ramps and the like. Where motor traffic is fast and heavy, and bicyclists must cross traffic lanes to continue on their route, I think that it is reasonable to consider alternatives to the standard vehicular movements. Clearly there is a problem, but I am not at all convinced that the blue lane is the solution. I suggest looking into other possible solutions which could make the actual merge/weave/crossing movement less difficult, or avoid it entirely. But what should these alternatives be? Preferably, they should provide alternative routes; typically, a vehicular route and a properly-designed off-road trail or pedestrian route -- not reduce caution or induce non-standard traffic movements. Neither should the atlernative routes be mandatory, delaying both motorists and bicyclists regardless of conditions. The abilities of bicyclists vary greatly, as does the speed and volume of motor traffic. It is inefficient to require bicyclists always to follow a slower, non-vehicular route when the vehicular route is difficult only for some bicyclists at some times. The Portland blue lane arrangements increase delays somewhat for bicyclists, and considerably more for motorists, and make the delays mandatory at all times a bicyclist is present. The nonstandard, non-vehicular movement may also result in failure to yield for a motorist unfamiliar with the blue lanes who expects normal rules to apply, or a local bicyclist who expects motorists to yield even where there are no "blue lanes". John Forester has analyzed the Portland study in more depth. The Portland study and Forester's analysis are available online. A counterexampleAs a counterexample to the blue lane installations, consider the image below from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) bicycle facilities guide. The sign at the right side reads "begin right turn lane, yield to bikes." The sign which is improperly used at Cambridge, Massachusetts blue lane installation would be appropriate here; both signs have the same significance. In the photo below, the lane to the left of the right turn lane is continuous. Unlike in the Cambridge blue lane installation, a motorist who is unable to merge into the right turn lane may continue across the intersection in the through lane. A motorist may need to do this because the right turn lane is be choked with other vehicles, or to avoid a collision with another vehicle. |

Even the example shown in the illustration still has some problems. The merge area is still too overdefined for the right-turning motorist, and too short. In order to ride defensively and discourage a right-turning motorist from a late merge and "right hook", a bicyclist would have to be somewhat to the left of the painted "bike lane" area. But this installation conforms much more closely to standard traffic-engineering principles than the blue lane installation does. Thanks to Ken O'Brien, Trevor Bourget, Fred Oswald, Kat Iverson and others, for comments and suggestions. |

| Top: Home Page Up: Bicycle facilities |

Contents copyright 2002, John S. Allen, |